Uno spazio dove si parli e racconti degli usi e costumi del periodo storico di fine XIV secolo: è quanto troverete su lextra.news grazie alla disponibilità, passione e competenza dei componenti dell’associazione Scudo e Spada, già molto attivi sul territorio con attività di didattica, laboratori ed accampamenti medievali.

di Azzurra Guido

curatrice storica “Associazione Scudo e Spada”

Il Bene e il Male sono concetti a cui l’uomo ha cercato di dare una definizione fin dall’alba dei tempi. Se la filosofia, sia dal punto di vista metafisico che morale, è andata nel corso dei secoli verso la consapevolezza di come l’interpretazione di questi sia inevitabilmente soggettiva e non sia possibile darne una definizione assoluta, le grandi religioni, in particolare i monoteismi, si sono trovati nella difficile posizione di spiegare il paradosso del Male di fronte all’affermazione dell’esistenza di una divinità buona, onnipotente e onnisciente. Se, infatti, le religioni politeiste sono popolate di dei ambivalenti o incuranti delle vicende e dei problemi degli esseri umani, l’idea di una lotta del Bene contro il Male, che si svolge nel corso della storia, è centrale nei credi detti abramitici (Ebraismo, Cristianesimo, Islam). Se da una parte esiste il Dio giusto, amorevole e compassionevole, pronto ad intervenire con la Provvidenza in aiuto dei bisognosi, dall’altra si viene a creare la figura dell’antagonista, il Signore del Male, che, da creatura divina egli stesso, assumerà le caratteristiche di una ribellione estrema nei confronti dell’ordine costituito. Questa figura è ovviamente il Diavolo.

La parola diavolo proviene dal verbo greco “diaballo” che significa “mettersi di traverso” e, in senso metaforico, “calunniare”. Con l’aggettivo “diabolos” si indicava un calunniatore, o un qualcosa di diffamatorio, e questo termine fu utilizzato nella Septuaginta, ossia la traduzione in greco della Bibbia che la tradizione vuole opera di 72 saggi di Alessandria d’Egitto (da cui il nome che significa “dei Settanta”) per tradurre la parola ebraica Satan. Il termine biblico “ha-satan” significa originariamente “avversario”, “colui che si oppone” e, per estensione, “nemico”; lo si trova nel Libro di Giobbe come qualifica di un angelo sottomesso a Dio che riveste il compito di capo accusatore della corte divina. Non un personaggio malvagio, quindi, privo di potere finchè gli umani non compiono azione maligne. Già nella Torah, la sua figura diventa ispirazione per le inclinazioni al male del popolo eletto, spingendolo, ad esempio, alla costruzione del vitello d’oro mentre Mosè è sul Sinai. A partire da qui, il Cristianesimo crea un’identificazione tra figure diverse: il Diavolo, Satana e Lucifero, l’angelo caduto. Il risultato è un essere che odia la creazione e l’intera umanità, il cui unico scopo è quello di operare con menzogne ed inganni affinchè l’uomo si allontani da Dio. E’ il serpente tentatore del giardino dell’Eden ed appare frequentemente nei Vangeli, configurandosi, nell’Apocalisse, come l’Anticristo. In questi testi è ancora più forte l’influenza dei culti dualistici orientali come il Mitraismo e, ancora di più, il Mazdeismo (Zoroastrismo): molti studiosi ritengono che il Diavolo cristiano si sia originato da Angra Mainyu e dal suo esercito di deeva, demoni, principio del male e portatore di distruzione, contrapposto al dio buono della luce Ahura Mazda.

Una presenza, quella del Diavolo, che si va quindi definendo gradualmente tramite apporti principalmente iranici e persiani, giungendo, tramite la predicazione dei primi discepoli cristiani, nel cuore dell’Europa. Ed è qui che conosce la sua fortuna grazie al “fatale incontro” con il Medioevo. Jacques Le Goff, uno dei più grandi studiosi dell’epoca medievale afferma, infatti, che “il Diavolo è stato la grande creazione del Cristianesimo durante il Medioevo”. Questo perché, tale figura, non ancora ben delineata ma dalla chiara connotazione, divenne funzionale al programma politico del potere ecclesiastico nel momento di dover decidere ciò che doveva essere considerato deviante e peccaminoso. Ed essendo la Chiesa perfettamente consapevole di possedere un ruolo formativo ed educativo nei confronti di un pubblico, quello dei fedeli, prevalentemente analfabeta, fece un uso massiccio di immagini, creando così una precisa iconografia della figura diabolica in cui elementi e colori divennero simboli per trasmettere messaggi agli spettatori. Ed essendo la paura del peccato quella che ha più ossessionato l’uomo medievale, questo tema si presentò in maniera insistente nell’arte e nella letteratura.

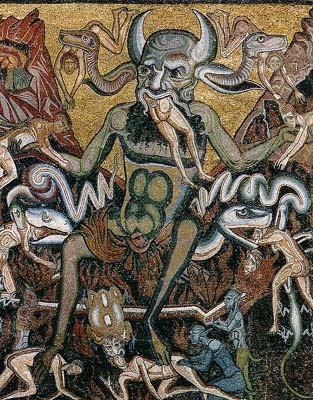

Nella sopraccitata Apocalisse, Satana viene descritto come un drago, un mostro con sette teste e dieci corna. L’immagine viene poi semplificata, conservando tuttavia l’attributo delle corna come simbolo di potere e richiamo agli dei della fertilità del mondo pagano. Non è un’immagine fissa perchè ha la capacità di trasformarsi ed assumere aspetti molteplici, utili al fine di ingannare. Per questo lo troviamo ritratto come un vecchio dalla barba bianca nel mosaico del Duomo dell’Isola di Torcello e come una bestia dotata di una fisicità mostruosa ed esagerata nel Mosaico del Giudizio del Battistero di San Giovanni a Firenze, dotata di tutti gli attributi tipici, ossia le corna, la barba nera e i serpenti. O ancora nel Giudizio Universale di Giotto nella cappella degli Scrovegni di Padova, dove è obeso, livido, animalesco, attorniato da serpi mostruose e da demoni sadici. Sia come tentatore, per cui appare nelle sembianze di un serpente o di una donna o di un viandante che spinge i peccatori a stipulare patti, che come torturatore infernale, la sua raffigurazione è basata sul concetto di diversità, di stravolgimento dei connotati umani e divini, di rovesciamento.

L’arte paleocristiana e quella successiva fino all’anno Mille prediligono le fattezze umanoidi, per cui il demonio è a volte un vecchio, a volte un essere piccolo e deforme, quasi un folletto maligno, con occhi di fuoco e capelli scuri, a volte serpentini, artigli ai piedi e naso lungo e ricurvo, particolare connesso allo stereotipo razziale dell’ebreo; a partire dall’XI secolo, invece, l’essere mostruoso, ibrido uomo e bestia, con coda, barba e zampe caprine, corna ed ali di pipistrello prevale, diventando sempre più grottesco. I suoi colori inizialmente sono il nero delle tenebre, il blu e il viola poiché, secondo la dottrina galenica, esso era costituito di aria pesante, densa e scura al contrario degli angeli, creature di fuoco etereo e, di conseguenza, rosse e bianche; il rosso diventa colore demoniaco, associato al sangue, alla lussuria e alle fiamme dell’Inferno solo nel tardo Medioevo; rare sono le presenze dei colori marrone e giallo pallido, che connotano i malati e i morti.

Fondamentale per l’immagine artistica e letteraria del Diavolo è la Visio Tnugdali, o Visione di Tnugdalo, testo del XII secolo che racconta della visione ultraterrena del cavaliere irlandese Tnugdalo: scritto in latino dal monaco irlandese Marcus (conosciamo solo il suo nome da monaco) nel monastero di Ratisbona, in Germania, narra le vicende dell’orgoglioso cavaliere che, rimasto incosciente per tre giorni, viene guidato da un angelo tra gli orrori dell’Inferno, di cui sperimenta alcuni tormenti, e le meraviglie del Paradiso. L’opera ebbe un successo incredibile, tanto che al XV secolo era già stato tradotto in quindici lingue diverse, tra cui il bielorusso e l’islandese, dovuto principalmente alle accurate descrizioni, in cui indulge nei particolari raccapriccianti, tra cui quella di Satana, presentato come un mostro che divora le anime e le espelle sul ghiaccio.

Il Diavolo si fa proiezione delle angosce legate alla morte e al senso di colpa, alla paura del peccato; i demoni sono deformi e terribile, maleodoranti, che soffiano fuoco dalla bocca e dalle narici. Rappresenta il sovvertimento delle leggi della natura, la sregolatezza e la bestialità: è un essere vorace che cattura e divora, immagine che sarà evocata dal lupo mangiatore di uomini del folklore e delle fiabe, dal licantropo e dal vampiro. Ogni visione dell’Inferno ormai è accompagnata indissolubilmente dalla presenza di Satana, nelle arti figurative come nella letteratura. Eccolo comparire, quindi, nel Libro delle Tre Scritture di Bonvesin De La Riva, nel De Babilonia Civitate Infernali di Giacomino da Verona e nell’Inferno di Dante Alighieri, tra le cui mani passò probabilmente la Visio Tnugdali. Il suo Diavolo ha tre bocche con cui maciulla i tre traditori più famosi: Giuda, Bruto e Cassio. Intrappolato con metà del corpo nel ghiaccio, le sue sei ali pesanti da pipistrello, simbolo di tenebre e cecità, non possono volare nell’aria gelida. E’ la materia, il Mostro, la negazione dello Spirito: il simbolo del Nulla che divora, piangendo lacrime di rabbia impotente.

***

Good and Evil are concepts that man has tried to define since the dawn of time. If philosophy, both metaphysical and moral, has gone over the centuries to the awareness of how the interpretation of these is inevitably subjective and it is not possible to give an absolute definition, the great religions, in particular the monotheisms, found themselves in the difficult position of explaining the paradox of evil in the face of the affirmation of the existence of a good, omnipotent and omniscient divinity. If, in fact, polytheistic religions are populated with ambivalent or careless of the vicissitudes and problems of human beings, the idea of a struggle of Good against Evil, which takes place throughout history, is central to the so-called Abrahamic creeds (Judaism, Christianity, Islam). If on the one hand there is the right, loving and compassionate God, ready to intervene with Providence to help the needy, on the other hand the figure of the antagonist, the Lord of Evil, comes to be created, who, from the divine creature himself, will take on the characteristics of an extreme rebellion against the established order. This figure is obviously the Devil.

The word devil comes from the Greek verb “diaballo” which means “to stand in the way” and, metaphorically, “to slander”. With the adjective “diabolos” it indicated a calumniator, or something slanderous, and this term was used in the Septuagint, that is the Greek translation of the Bible that tradition wants the work of 72 sages of Alexandria of Egypt (hence the name meaning “of the Seventy”) to translate the Hebrew word Satan. The biblical term “ha-Satan” originally means “adversary”, “one who opposes” and, by extension, “enemy”; it is found in the Book of Job as a qualification of an angel submissive to God who is the chief accuser of the divine court. Not an evil character, therefore, powerless until humans perform evil action. Already in the Torah, his figure becomes inspiration for the inclinations to evil of the chosen people, pushing him, for example, to the construction of the golden calf while Moses is on Sinai. From here, Christianity creates an identification between different figures: the Devil, Satan and Lucifer, the fallen angel. The result is a being who hates creation and all humanity, whose sole purpose is to work with lies and deception so that man may turn away from God. It is the tempting serpent of the Garden of Eden and frequently appears in the Gospels, configuring itself, in the Apocalypse, as the Antichrist. In these texts the influence of Eastern dualistic cults such as Mithraism and, even more, Mazdeism (Zoroastrianism) is even stronger: many scholars believe that the Christian Devil originated from Angra Mainyu and his army of deeva, demons, principle of evil and bearer of destruction, opposed to the good god of light Ahura Mazda.

A presence, that of the Devil, which is then gradually defining itself through contributions mainly Iranian and Persian, arriving, through the preaching of the first Christian disciples, in the heart of Europe. And it is here that he knows his fortune thanks to the “fatal encounter” with the Middle Ages. Jacques Le Goff, one of the greatest scholars of the medieval era, states, in fact, that “the Devil was the great creation of Christianity during the Middle Ages”. This is because this figure, not yet well outlined but with a clear connotation, became functional to the political program of ecclesiastical power at the time of having to decide what was to be considered deviant and sinful. And since the Church was fully aware of having a formative and educational role in relation to an audience, that of the faithful, predominantly illiterate, made a massive use of images, thus creating a precise iconography of the diabolical figure in which elements and colors became symbols to convey messages to viewers. And being the fear of sin the one that most haunted medieval man, this theme presented itself insistently in art and literature.

In the above-mentioned Revelation, Satan is described as a dragon, a monster with seven heads and ten horns. The image is then simplified, however preserving the attribute of the horns as a symbol of power and reference to the gods of the fertility of the pagan world. It is not a fixed image because it has the ability to transform and assume multiple aspects, useful in order to deceive. For this reason we find him portrayed as an old man with a white beard in the mosaic of the Cathedral of the Island of Torcello and as a beast endowed with a monstrous and exaggerated physicality in the Mosaic of Judgement of the Baptistery of San Giovanni in Florence, endowed with all the typical attributes, the horns, the black beard and the snakes. Or again in the Last Judgement of Giotto in the chapel of the Scrovegni of Padua, where he is obese, livid, animalistic, surrounded by monstrous snakes and sadistic demons. Whether as a tempter, so appearing in the guise of a snake or a woman or a traveler who pushes sinners to enter into covenants, or as an infernal torturer, his depiction is based on the concept of diversity, of distortion of human and divine connotations, overturning.

Early Christian art and the one after that until the year 1000 prefer humanoid features, so the devil is sometimes an old, sometimes a small and deformed being, almost an evil elf, with fiery eyes and dark hair, sometimes snakes, claws at the feet and a long, curved nose, particularly related to the racial stereotype of the Jew; from the eleventh century, on the other hand, the monstrous, hybrid man and beast, with tail, beard and goat legs, horns and bat wings prevails, becoming more and more grotesque. Its colors initially are the black of darkness, the blue and the violet because, according to the Galenic doctrine, it was made of heavy air, dense and dark as opposed to angels, creatures of ethereal fire and, consequently, red and white; the red becomes demonic color, associated with the blood, lust and flames of Hell only in the late Middle Ages; rare are the presences of brown and pale yellow, which connote the sick and the dead.

Fundamental to the artistic and literary image of the Devil is the Visio Tnugdali, or Vision of Tnugdalo, text of the twelfth century that tells of the otherworldly vision of the Irish knight Tnugdalo: written in Latin by the Irish monk Marcus (we only know his name as a monk) in the monastery of Regensburg, Germany, tells the story of the proud knight who, remained unconscious for three days, is led by an angel among the horrors of Hell, of which he experiences some torments, and the wonders of paradise. The work had an incredible success, so much so that by the fifteenth century it had already been translated into fifteen different languages, including Belarusian and Icelandic, due mainly to the accurate descriptions, in which it indulges in the gruesome details, including that of Satan, presented as a monster that devours souls and expels them on ice.

The Devil makes projection of the anguish related to death and guilt, to the fear of sin; the demons are deformed and terrible, smelly, that blow fire from the mouth and nostrils. It represents the subversion of the laws of nature, the recklessness and bestiality: it is a voracious being that captures and devours, an image that will be evoked by the wolf eater of men of folklore and fairy tales, by the werewolf and the vampire. Every vision of Hell is now indissolubly accompanied by the presence of Satan, in the figurative arts as in literature. Here he appears, then, in the Book of the Three Scriptures by Bonvesin De La Riva, in the De Babilonia Civitate Infernali by Giacomino from Verona and in the Inferno by Dante Alighieri, whose hands probably passed the Visio Tnugdali. His Devil has three mouths with which to crush the three most famous traitors: Judas, Brutus and Cassius. Trapped with half his body in the ice, his six heavy bat wings, symbol of darkness and blindness, can not fly in the cold air. It is the Matter, the Monster, the negation of the Spirit: the symbol of Nothing that devours, weeping tears of powerless anger.

FONTI

J.B Russell, Il Diavolo nel Medioevo, Laterza, Roma/Bari, 1982

Il Diavolo nel Medioevo. Atti del XLIX Convegno Storico internazionale di Todi, 14-17 ottobre 2012, Spoleto, 2013

G. Minois, Piccola Storia del Diavolo, Il Mulino, Bologna, 1999

R. Astori, Il problema del Male nel Medioevo: le figure diaboliche nella riflessione teologica e nel folklore, in Storiadelmondo n.19, 5 gennaio 2004

J. Burton Russel, The Devil: Perception of Evil from Antiquity to Primitive Christianity, New York, 1977

E. Pagel, The Origin of Satan, New York, 1995

Dante Alighieri, Divina Commedia: Inferno

Bonvesin de La Riva, Libro delle Tre Scritture, a cura di Matteo Leonardi, Ravenna 2014

Giacomino Da Verona, De Babilonia Civitate Infernali

A. Wagner, Visio Tnugdali Lateinisch und Altdeutsch, Hildescheim, New York, 1989.