Uno spazio dove si parli e racconti degli usi e costumi del periodo storico di fine XIV secolo: è quanto troverete su lextra.news grazie alla disponibilità, passione e competenza dei componenti dell’associazione Scudo e Spada, già molto attivi sul territorio con attività di didattica, laboratori ed accampamenti medievali.

di Azzurra Guido

curatrice storica “Associazione Scudo e Spada”

Il Medioevo è stato un periodo di contrasti molto forti dal punto di vista storico, politico e culturale, caratterizzato da una decisa spinta verso il rinnovamento e, allo stesso tempo, dal radicarsi di alcune posizioni che gli hanno fatto guadagnare la cattiva reputazione di epoca buia e arretrata.

Non è assolutamente possibile guardare agli eventi e alla società medievale senza tenere conto di quelli che sono stati i dissidi più profondi, per molti aspetti intimamente legati tra loro, ossia quello tra Impero/potere secolare e Chiesa/potere spirituale e l’altro, interno a quest’ultimo, tra santità ed eresia.

L’argomento è estremamente complesso e vasto, destinato a non risolversi nel corso di un unico periodo storico, anzi: la questione religiosa medievale è stata la base per la Riforma Protestante del XVI secolo e motivo di riflessione per la conseguente Controriforma.

La prima tappa fondamentale di questo percorso è l’Editto di Milano, chiamato anche Editto di Tolleranza, con cui, nel 313, l’imperatore d’Occidente Costantino e quello d’Oriente Licinio, nell’ottica di ottenere una politica religiosa comune alle due parti dell’Impero, concessero di fatto la libertà di venerare le proprie divinità a tutti i cittadini, compresi i cristiani. In particolare, in materia di religione, Costantino seguì una linea di compromesso per cui non proibì mai il culto pagano, praticato dalla maggioranza dei senatori imperiali, pur cercando un dialogo più stretto con le correnti tendenti al monoteismo del paganesimo stesso, e, allo stesso tempo, rese la domenica giorno festivo, vietò la magia e la divinazione privata e permise al clero di assumere posizioni sociali elevate. Inoltre, indisse, al fine di raggiungere l’unità dogmatica, il Concilio di Nicea del 325, il primo della Cristianità, che si occupò di organizzare la gerarchia ecclesiastica e di fissare le regole del culto, il cosiddetto “credo niceno”, che, nel 380 con l’Editto di Tessalonica fu dichiarato dagli imperatori Teodosio I e Graziano religione di stato, cattolico, ossia universale, ed ortodosso, cioè corretto.

Già durante questo primo concilio, tuttavia, si presentò la necessità di ottenere un confronto tra diverse fazioni. Lungi dall’essere un blocco unitario, l’insieme dei fedeli cristiani si articolava, fin da allora, in gruppi diversi principalmente per questioni filosofiche inerenti alla reale natura della figura di Cristo, la sua divinità, i rapporti con il Giudaismo ed il monoteismo precristiano. Si tratta di insegnamenti teologici conosciuti come dottrine cristologiche che daranno luogo alle chiese scismatiche, la più conosciuta delle quali è, probabilmente, l’Arianesimo, i cui adepti sostenevano la divinità della sola figura del Padre, relegando Gesù alla dimensione umana, che ebbe un’enorme diffusione tra le popolazioni barbariche dei Goti, Vandali e Longobardi.

Il problema, quindi, di elementi di separazione, di protesta e di rinnovamento, era insito nella Chiesa fin dai suoi inizi ed i rapporti con essi erano destinati a diventare più tesi con il passare degli anni, fino alle estreme conseguenze. Momento fondamentale è l’elezione al soglio pontificio di Gelasio I (492-496), il primo ad aver affermato il primato della Chiesa sullo Stato, in particolare della Sede romana, ed aver gettato le basi per il potere temporale del papa. La chiesa romana si sentiva, in questo modo, tenuta a rispettare le leggi imperiali solo nella misura in cui l’imperatore ammetteva la propria subordinazione alla volontà del pontefice. Sempre secondo Gelasio, l’imperatore non poteva in alcun modo intervenire nelle questioni di fede ed i credenti gli dovevano obbedienza solo in quanto fiduciario della Chiesa, ponendo le basi per il potente strumento politico della scomunica. Questo compromettersi sempre più evidente delle più alte gerarchie ecclesiastiche con la politica e la materialità del potere temporale, spinse gruppi sempre più consistenti a ribellarsi all’ortodossia e ad organizzarsi in movimenti di aperta protesta. Tratti comuni a tutti sono la ricerca di un risveglio spirituale, la critica aspra verso la ricchezza eccessiva del clero, l’allontanamento dalla Scritture e il coinvolgimento politico. Alcuni di questi furono considerati riformatori, altri condannati come eretici, alcune volte entrambe le cose a seconda del mutare del momento politico; la differenza tra gli uni e gli altri fu determinata dall’impatto sociale che certe idee potevano produrre per cui coloro che osavano schierarsi contro l’autorità religiosa o tentavano di produrre modifiche sociali venivano perseguitati.

Tra i primi e di importanza fondamentale per l’influenza esercitata sull’eresia per antonomasia del Medioevo, quella catara, è il movimento dei Bogomili, dal nome del suo fondatore, il prete Bogomil, sorto nei Balcani nel X secolo e diffusosi in Serbia e in Bosnia. Fortemente influenzato dalla filosofia manichea, il Bogomilismo sosteneva l’esistenza di due principi opposti ben definiti, il Bene e il Male. Il figlio primogenito di Dio era Satanael, una creatura ribelle che aveva creato il mondo materiale e gli esseri umani, destinati, quindi, ad essere schiavi del Male, fino alla venuta di Cristo, il secondogenito, giunto a liberare il principio spirituale contenuto nell’uomo. La materia, quindi, era da combattere in ogni modo: rifiutavano i rapporti sessuali, il matrimonio, non bevevano vino ed erano vegetariani poichè la carne, le uova e il latte erano considerati prodotti dell’atto sessuale. Odiavano la croce, simbolo dell’apparente omicidio di Cristo, e rifiutavano le immagini sacre; ammettevano solo il sacramento del battesimo e non riconoscevano né le festività ecclesiastiche né le preghiere, fatta eccezione per il Padre Nostro. Il loro capo Basilio fu invitato nel 1118 ad esporre le proprie idee di fonte all’imperatore d’Oriente, Alessio Comneno, che lo fece imprigionare. Essendo egli stesso un teologo, tentò di convincere Basilio ad abiurare ma, al suo rifiuto, lo condannò al rogo e dichiarò eretici i suoi seguaci. Avendo rinnegato l’Antico Testamento, essi avevano prodotto, di contro, molti testi apocrifi tra cui l’Interrogatio Iohannis (Le domande di Giovanni Evangelista) che dalla Bulgaria giunse in Italia e divenne il Secretum, il Libro Segreto degli Albigesi, la base dottrinale del Catarismo.

I Catari, dal greco antico “katharos” “puro”, conosciuti anche come Albigesi dal nome della cittadina francese Albi, costituirono un movimento religioso sorto nel XII secolo in Occitania, nei territori della Linguadoca. Come sopra sottolineato, la loro dottrina era di derivazione bogomila e manichea, riprendendo tutti gli elementi che le caratterizzavano. I Catari credevano fortemente nel dualismo tra il Re d’Amore, ossia Dio, e il Re del Male, Rex mundi, ossia l’Anti-dio, signore della materialità, il creatore del mondo che corrispondeva, quindi, al Dio di cui si narra nella Bibbia. La Chiesa corrotta ed attaccata ai beni materiali, era, quindi, al servizio di Satana e da qui la necessità di creare una propria istituzione ecclesiastica. I sacramenti erano rifiutati nel loro complesso, compresi battesimo, eucarestia e matrimonio. La massima aspirazione era la morte, vittoria finale del Bene, che liberava lo spirito ed era indicata come ideale quella avvenuta per fame.

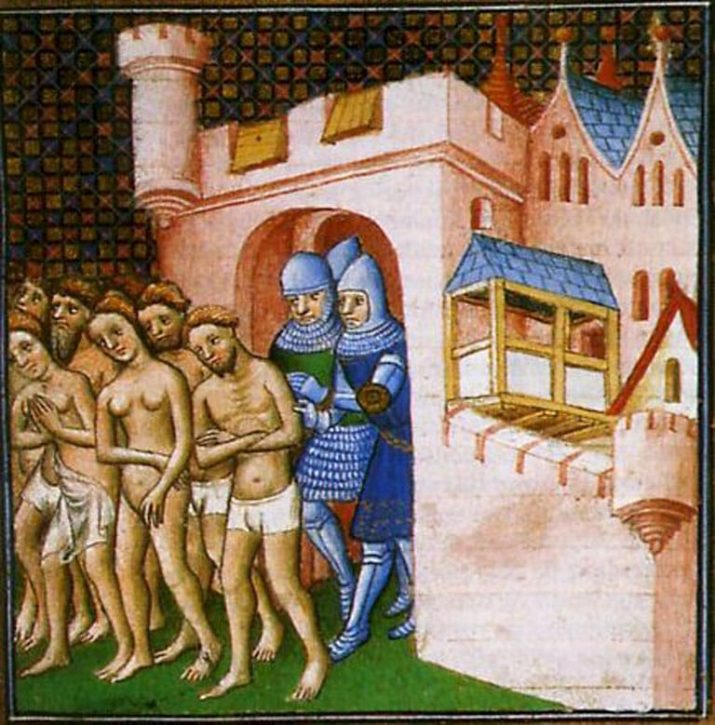

Contro i Catari, comprensibilmente dichiarati eretici, la Chiesa tentò inizialmente una strada non violenta; in particolare, va menzionata l’opera di Domenico di Guzman che concepì una predicazione volta a contrastarli con i loro stessi strumenti, basata su povertà, umiltà e carità che poi userà, circa 10 anni dopo, per fondare l’ordine domenicano. Al fallimento di questi primi approcci, papa Alessandro III li condannò, colpendoli con l’anatema, una sorta di maledizione più potente della scomunica e Gregorio IX creò il tribunale dell’Inquisizione per debellare definitivamente l’eresia catara. Innocenzo III, infine, bandì contro di loro, nel 1203, una crociata, la prima fatta da cristiani contro altri cristiani, che si rivelò un vero e proprio genocidio e si concluse nel 1244 con la caduta dell’ultima roccaforte di Montsegur. È interessate notare come vi fu una coincidenza sia geografica che temporale tra eresia catara e poesia trobadorica: seppure si trattasse di mondi diametralmente opposti e incompatibili, le loro vicende finirono per intrecciarsi e molti furono i trovatori che si scagliarono duramente contro i metodi violenti e sanguinari utilizzati dalla Chiesa, al punto che la fine dei Catari segnò anche la fine della poesia in lingua provenzale.

Stesso destino cruento toccò ai Dolciniani e al loro fondatore Fra’ Dolcino. Entrato all’inizio nel movimento degli Apostoli, in sospetto di eresia nel 1286 e condannati e repressi definitivamente nel 1300, Dolcino continuò una predicazione apertamente ostile nei confronti della Chiesa di Roma e di papa Bonifacio VIII. I principi su cui si fondava il suo credo prevedevano digiuni e preghiere, lavoro e richieste di elemosina, senza l’imposizione del celibato. L’obbedienza dei Dolciniani era verso le scritture mentre era considerato doveroso disobbedire al papa, vista la sua lontananza dai precetti evangelici. Nonostante l’affermazione della necessità di una vita condotta in povertà, si abbandonarono a volte a rapine e saccheggi più consistenti di quanto fosse sufficiente per la sopravvivenza e, per questo motivo, si inimicarono anche un‘ampia fetta di popolazione. Contro di loro si mosse il vescovo di Vercelli che proclamò una nuova crociata; nel 1307 furono costretti alla resa, catturati e uccisi i seguaci, condannato al rogo Dolcino.

Un fato diverso, invece, fu quello dei Valdesi, confessione del XII secolo che deve il suo nome a Valdo di Lione, il suo fondatore, che fece tradurre i testi sacri in francese per renderli accessibili a tutti. Erano un movimento pauperistico, cristiano e laico, di poco precedente alla predicazione di Francesco d’Assisi e cercarono fin dal Terzo Concilio Laterano con papa Alessandro III di ottenere l’approvazione ecclesiastica. Nonostante il pontefice apprezzasse i principi fondanti a cui si ispiravano, non era possibile accettare che dei laici leggessero la Bibbia e, tantomeno, che predicassero, quindi negò loro il riconoscimento. Nel 1184 furono scomunicati ma riuscirono a sopravvivere durante l’Età dei Comuni in terra lombarda e, nonostante le persecuzioni dell’Inquisizione, nascondendosi nella clandestinità, giunsero al XVI quando aderirono alla Riforma Protestante Calvinista, costituendo una Chiesa attiva ancora oggi.

Impossibile in questa sede trattare di tutti gli aspetti legati al concetto di eresia e prendere in esame ogni movimento di ribellione, più o meno pacifica, nei confronti della religione e dell’istituto ecclesiastico. Si può notare, comunque, come tutte le eresie medievali erano nate da una sfasatura interna al Cristianesimo stesso, l’antitesi che si era creata tra il messaggio rivoluzionario di Gesù e l’interpretazione e l’uso che ne fece la Chiesa. Nel corso del suo affermarsi come religione di stato, il Cristianesimo delle origini aveva perso elementi che erano stati fondamentali per la sua diffusione, come l’escatologia, il profetismo, l’apocalittica, il distacco dalle cose terrene, andando verso la politica, “sporcandosi le mani”. Allo stesso tempo, il fallimento di praticamente tutte le eresie medievali è dovuto all’incapacità di rinunciare alla religione come unico metodo di risoluzione delle problematiche sociali, senza riuscire così a competere con l’ideologia dominante.

***

The Middle Ages was a period of very strong contrasts from the historical, political and cultural point of view, characterized by a determined drive towards renewal and, At the same time, by taking root some positions that have earned him the bad reputation of a dark and backward era.

It is absolutely impossible to look at events and medieval society without taking into account what were the deepest differences, in many respects intimately linked to each other, namely that between empire/secular power and church/spiritual power and the other, between holiness and heresy.

The subject is extremely complex and vast, destined not to be resolved during a single historical period, on the contrary: the medieval religious question was the basis for the Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth century and a reason for reflection for the subsequent Counter-Reformation.

The first fundamental stage of this journey is the Edict of Milan, also called the Edict of Tolerance, with which, in 313, the Emperor of the West Constantine and that of the East Licinius, with the aim of obtaining a religious policy common to both parts of the Empire, granted in fact the freedom to venerate their deities to all citizens, including Christians. In particular, in matters of religion, Constantine followed a compromise line whereby he never forbade pagan worship, practiced by the majority of imperial senators, while seeking a closer dialogue with the currents tending to the monotheism of paganism itself, and, at the same time, made Sunday a public holiday, forbade magic and private divination, and allowed the clergy to assume high social positions. In addition, he called, in order to achieve dogmatic unity, the Council of Nicaea in 325, the first of Christianity, which was responsible for organizing the ecclesiastical hierarchy and fixing the rules of worship, the so-called “Nicene creed” which, in 380 with the Edict of Thessalonica was declared by the emperors Theodosius I and Gratian state religion, Catholic, or universal, and orthodox, that is correct.

Already during this first council, however, there was a need to obtain a confrontation between different factions. Far from being a unitary bloc, the whole of the Christian faithful has been articulated, since then, in different groups mainly for philosophical questions concerning the real nature of the figure of Christ, his divinity, relations with Judaism and pre-Christian monotheism. These are theological teachings known as Christological doctrines which will give rise to schismatic churches, the best known of which is probably Arianism, whose adepts supported the divinity of the Father alone, relegating Jesus to the human dimension, that had a huge spread among the barbarian populations of the Goths, Vandals and Lombards.

The problem, therefore, of elements of separation, protest and renewal, was inherent in the Church from its beginnings and relations with them were destined to become more tense with the passing of the years, to the extreme consequences. Fundamental moment is the election to the papal throne of Gelasius I (492-496), the first to have asserted the primacy of the Church over the State, in particular the Roman See, and to have laid the foundations for the temporal power of the pope. The Roman church felt, in this way, obliged to respect the imperial laws only to the extent that the emperor admitted his own subordination to the will of the pontiff. According to Gelasius, the emperor could in no way intervene in matters of faith and believers owed him obedience only as a trustee of the Church, laying the foundations for the powerful political instrument of excommunication. This increasingly evident compromise of the highest ecclesiastical hierarchies with the politics and materiality of temporal power, pushed increasingly consistent groups to rebel against orthodoxy and to organize themselves in movements of open protest. Common traits to all are the search for a spiritual awakening, the harsh criticism of the excessive wealth of the clergy, the distancing from the Scriptures and political involvement. Some of these were considered reformers, others condemned as heretics, sometimes both depending on the changing of the political moment; The difference between them was determined by the social impact that certain ideas could produce, so that those who dared to stand against religious authority or attempt to produce social changes were persecuted.

Among the first and of fundamental importance for the influence exerted on the heresy par excellence of the Middle Ages, the Cathar, is the movement of Bogomili, from the name of its founder, the priest Bogomil, born in the Balkans in the tenth century and spread in Serbia and Bosnia. Strongly influenced by Manichaean philosophy, Bogomilism held the existence of two well-defined opposing principles, Good and Evil. The first-born son of God was Satanael, a rebellious creature who had created the material world and human beings, destined, therefore, to be slaves of evil, until the coming of Christ, the second-born, came to free the spiritual principle contained in man. The matter, therefore, was to be fought in every way: they refused sexual relations, marriage, they did not drink wine and they were vegetarians since meat, eggs and milk were considered products of the sexual act. They hated the cross, symbol of the apparent murder of Christ, and rejected the sacred images; They admitted only the sacrament of baptism and did not recognize either the ecclesiastical festivities or the prayers, except for the Our Father. Their leader Basil was invited in 1118 to present his ideas to the Emperor of the East, Alexios Komnenos, who had him imprisoned. Being a theologian himself, he tried to convince Basil to abjure himself but, at his refusal, condemned him to the stake and declared his followers heretics. Having denied the Old Testament, they had produced, by contrast, many apocryphal texts including the Interrogatio Iohannis (The Questions of John the Evangelist) which from Bulgaria arrived in Italy and became the Secretum, the Secret Book of the Albigenses, the doctrinal basis of Catharism.

The Cathars, from the ancient Greek “katharos” “pure”, also known as Albigesi from the name of the French town Albi, constituted a religious movement born in the twelfth century in Occitania, in the territories of Languedoc. As noted above, their doctrine was of Bogomil and Manichean derivation, taking over all the elements that characterized them. The Cathars strongly believed in the dualism between the King of Love, that is, God, and the King of Evil, Rex mundi, that is the Anti-god, lord of materiality, the creator of the world that corresponded, therefore, to the God of which it is narrated in the Bible. The Church, corrupted and attached to material goods, was, therefore, at the service of Satan and hence the need to create its own ecclesiastical institution. The sacraments were rejected as a whole, including baptism, the Eucharist and marriage. The greatest aspiration was death, the final victory of Good, which liberated the spirit and was indicated as the ideal that occurred by hunger.

Against the Cathars, understandably declared heretics, the Church initially attempted a non-violent path; In particular, it is worth mentioning the work of Domenico di Guzman who conceived a preaching aimed at contrasting them with their own instruments, based on poverty, humility and charity which he then used, about 10 years later, to found the Dominican order. Upon the failure of these early approaches, Pope Alexander III condemned them, striking them with anathema, a kind of curse more powerful than excommunication, and Gregory IX created the tribunal of the Inquisition to finally eradicate the Cathar heresy. Finally, Innocent III banished against them, in 1203, a crusade, the first made by Christians against other Christians, which proved to be a real genocide and ended in 1244 with the fall of the last stronghold of Montsegur. It is interesting to note that there was a geographical and temporal coincidence between Cathar heresy and troubadour poetry: although these were diametrically opposite and incompatible worlds, Their vicissitudes eventually intertwined and many troubadours were the ones who hurled themselves harshly against the violent and bloody methods used by the Church, to the point that the end of the Cathars also marked the end of poetry in the Provençal language.

The same bloody fate befell the Dolcinians and their founder Fra’ Dolcino. At the beginning he entered the movement of the Apostles, suspected of heresy in 1286 and condemned and finally repressed in 1300, Dolcino continued an openly hostile preaching against the Church of Rome and Pope Boniface VIII. The principles on which his creed was founded provided for fasting and prayer, work and requests for alms, without the imposition of celibacy. The obedience of the Dolcinians was to the scriptures while it was considered dutiful to disobey the pope, considering his distance from the evangelical precepts. Despite the assertion of the need for a life in poverty, they sometimes indulged in robberies and looting more substantial than was sufficient for survival and, for this reason, they also antagonized a large slice of the population. The bishop of Vercelli came against them and proclaimed a new crusade; In 1307 they were forced to surrender, captured and killed the followers, condemned to the stake Dolcino.

A different fate, however, was that of the Waldenses, a confession of the twelfth century that owes its name to Walden of Lyon, its founder, who had the sacred texts translated into French to make them accessible to all. They were a pauperistic movement, Christian and lay, just before the preaching of Francis of Assisi and tried since the Third Lateran Council with Pope Alexander III to obtain ecclesiastical approval. Although the pontiff appreciated the founding principles that inspired them, it was not possible to accept that lay people read the Bible and, even less, that they preached, so he denied them recognition. In 1184 they were excommunicated but managed to survive during the Age of Commons in Lombardy and, despite the persecutions of the Inquisition, hiding in the underground, came to the sixteenth when they joined the Protestant Calvinist Reformation, constituting an active Church still today.

It is impossible here to deal with all the aspects related to the concept of heresy and to examine any movement of rebellion, more or less peaceful, towards religion and the ecclesiastical institute. It can be noted, however, that all the medieval heresies were born from a phase within Christianity itself, the antithesis that had arisen between the revolutionary message of Jesus and the interpretation and use that the Church made of it. In the course of its establishment as a state religion, the early Christianity had lost elements that had been fundamental to its spread, such as eschatology, prophetism, apocalyptic, detachment from earthly things, going toward politics, “getting his hands dirty”. At the same time, the failure of virtually all medieval heresies is due to the inability to renounce religion as the only method of solving social problems, thus failing to compete with the dominant ideology.

FONTI

E. Gavalotti, Cristianesimo Medievale, Ed. digitale homolaicus.com

U.Eco (a cura di), Il Medioevo. Barbari, cristiani, musulmani, Encyclomedia Publishers, 2010, Milano.

G. Merlo Grado, Eretici ed eresie medievali, Il Mulino, Bologna, 1989

W. Bauer, Orthodoxy and Heresy in Earliest Christianity, Fortress, Philadelphia, 1971

M. Mason, Eretgia. La crociata contro gli Albigesi tra storia, epica e lirica trobadorica, Il Cerchio, Rimini, 2014

A. Brenon, I Catari, storia e destino dei veri credenti, Convivio, Firenze, 1990

R. Orioli (a cura di), Fra Dolcino. Nascita, vita e morte di un’eresia medievale, Jaca Book, Milano, 2004

G. Tourn, I Valdesi nella storia, Claudiana, Torino, 1996